A huge part of my new job as a coach is to facilitate weekly inquiry team meetings with the algebra teachers I'm coaching. In some schools these teams are made up of just algebra teachers, because there are so many, and in other schools they are made up of a combination of algebra teachers and other math teachers who aren't teaching algebra.

When I started this job, I had never heard of capital "I" Inquiry, despite the fact that it's been a citywide mandate for a few years. It seemed pretty simple: look at student work and make instructional decisions based on it. We were told that teacher teams might be resistant because they'd been made to do some less useful version of Inquiry by their schools to meet the city mandate, or because the teachers who didn't teach algebra would push back on looking at work of students who weren't their own.

In my actual experience, it's just been hard to get down to the business of doing it. My teams have been legitimately baffled by other parts of the program and we've spent a lot of time just problem solving, delving more deeply into the work of planning on the unit and lesson levels and just using our time together to get more familiar with the performance tasks and formative assessment lessons we're using. There have been so many things we're doing for the first time that our Inquiry work has just been put on the side.

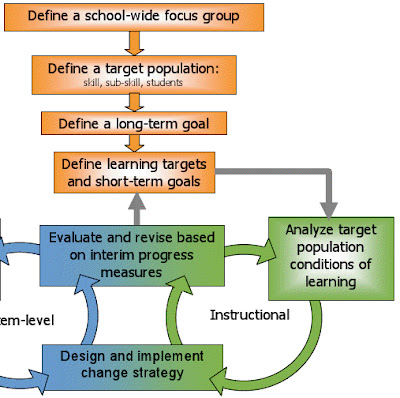

My boss insisted that this week, I start an inquiry cycle with my team. Here's what this looks like, according to the Inquiry Team Handbook, p.13

We start in the orange part of this diagram to set up our stage. In our case, the team is already defined as the school wide focus group, and the long term goals are already defined by the Common Core Mathematical Practice Standards. This week, the team defined it's target population. Each of the four teachers selected two students, who (based on student work which they shared with the team) are on the cusp of success: students who are just below passing, but who have good attendance and are making an effort.

Over the course of the next four weeks, the team will define a concrete and measurable short term goal for the target population to reach before Christmas break and then begin the green cycle, strategically intervening based on the evidence of student misunderstandings, using student work to assess the success of those interventions, and re-engaging each week to close the gap between the target population and the short term goal.

In the new year, we will start a new green cycle, either re-iterating around the same short term goal if we haven't been successful, or coming up with a new one.

The big idea here is that by focusing on the needs of just a couple of students that are just outside the sphere of success, teachers will better meet the needs of all their students. I have to be honest: I have not done this before, so I haven't seen it work, but I'm very curious. What I know is that looking at student work is remarkably rare. Teachers make statements all the time about what their students are and are not capable of and get optimistic or discouraged about what's coming based on experience (essential, useful, relevant) but not on concrete evidence. Teachers know many things about their students, but if they aren't looking at student work to determine whether or not students have learned something new between when they entered the classroom and when they left it, they are missing out on something essential and the students are suffering because of it.

I am encouraged by what this process is already drawing out of my teachers. It's hard for them to bring in student work. It's hard for them to identify or articulate what the mathematics is that their students can or can't do. It's hard for them to be willing to break down the overwhelming task of teaching 100 students all of algebra, and instead articulate one goal that they will get two students to accomplish in 4 weeks. But I am excited to see what happens: even if we fail miserably, even if our interventions are vague and our evidence is muddy and our results seem bleak - I think this is the process through which we will learn how to study student learning and productively respond to improve it.

The inquiry process with my teacher teams is working its way backwards and holding me more accountable in my parallel work with them as a coach. Having done just this small bit this week with my teachers, I have finally realized that I need to do the same thing as a coach: articulate my short term goals for each teacher and use evidence to inform my decision making about what to focus on with them and how to best support them in growing as teachers.

Pep talk, anyone?

Happy Thanksgiving!

When I started this job, I had never heard of capital "I" Inquiry, despite the fact that it's been a citywide mandate for a few years. It seemed pretty simple: look at student work and make instructional decisions based on it. We were told that teacher teams might be resistant because they'd been made to do some less useful version of Inquiry by their schools to meet the city mandate, or because the teachers who didn't teach algebra would push back on looking at work of students who weren't their own.

In my actual experience, it's just been hard to get down to the business of doing it. My teams have been legitimately baffled by other parts of the program and we've spent a lot of time just problem solving, delving more deeply into the work of planning on the unit and lesson levels and just using our time together to get more familiar with the performance tasks and formative assessment lessons we're using. There have been so many things we're doing for the first time that our Inquiry work has just been put on the side.

My boss insisted that this week, I start an inquiry cycle with my team. Here's what this looks like, according to the Inquiry Team Handbook, p.13

We start in the orange part of this diagram to set up our stage. In our case, the team is already defined as the school wide focus group, and the long term goals are already defined by the Common Core Mathematical Practice Standards. This week, the team defined it's target population. Each of the four teachers selected two students, who (based on student work which they shared with the team) are on the cusp of success: students who are just below passing, but who have good attendance and are making an effort.

Over the course of the next four weeks, the team will define a concrete and measurable short term goal for the target population to reach before Christmas break and then begin the green cycle, strategically intervening based on the evidence of student misunderstandings, using student work to assess the success of those interventions, and re-engaging each week to close the gap between the target population and the short term goal.

In the new year, we will start a new green cycle, either re-iterating around the same short term goal if we haven't been successful, or coming up with a new one.

The big idea here is that by focusing on the needs of just a couple of students that are just outside the sphere of success, teachers will better meet the needs of all their students. I have to be honest: I have not done this before, so I haven't seen it work, but I'm very curious. What I know is that looking at student work is remarkably rare. Teachers make statements all the time about what their students are and are not capable of and get optimistic or discouraged about what's coming based on experience (essential, useful, relevant) but not on concrete evidence. Teachers know many things about their students, but if they aren't looking at student work to determine whether or not students have learned something new between when they entered the classroom and when they left it, they are missing out on something essential and the students are suffering because of it.

I am encouraged by what this process is already drawing out of my teachers. It's hard for them to bring in student work. It's hard for them to identify or articulate what the mathematics is that their students can or can't do. It's hard for them to be willing to break down the overwhelming task of teaching 100 students all of algebra, and instead articulate one goal that they will get two students to accomplish in 4 weeks. But I am excited to see what happens: even if we fail miserably, even if our interventions are vague and our evidence is muddy and our results seem bleak - I think this is the process through which we will learn how to study student learning and productively respond to improve it.

The inquiry process with my teacher teams is working its way backwards and holding me more accountable in my parallel work with them as a coach. Having done just this small bit this week with my teachers, I have finally realized that I need to do the same thing as a coach: articulate my short term goals for each teacher and use evidence to inform my decision making about what to focus on with them and how to best support them in growing as teachers.

Pep talk, anyone?

Happy Thanksgiving!

No comments:

Post a Comment